From International Vision to Local Action

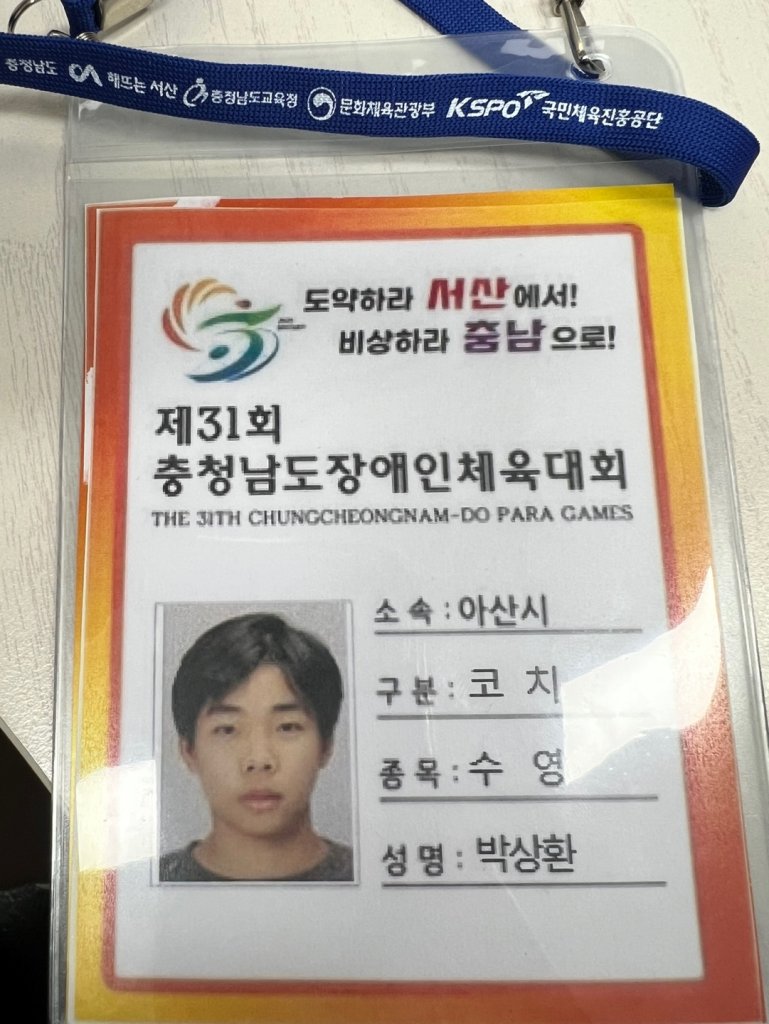

After months of international community engagement through Ubuntu Network and expanding advocacy networks at Seoul Africa Festival, May 2025 brought an opportunity to apply everything I’d learned closer to home. When the call came to volunteer as a swimming coach for the 31st Chungcheongnam-do Paralympic Games in Seosan, I knew this was a chance to bridge my growing understanding of sports psychology with direct support for Paralympic athletes in Korea.

The invitation came through my connection with the Asan City Paralympic Sports Association. Having established my credentials through St. Johnsbury’s swim team captaincy and demonstrated commitment to inclusive athletics through my Uganda work, I was asked to serve as a volunteer coach for young Paralympic swimmers representing Asan City.

Understanding the Paralympic Landscape in Korea

The 31st Chungcheongnam-do Paralympic Games, held from May 29-31, 2025, in Seosan City, was one of Korea’s largest regional Paralympic competitions. With 16 official sports and 1 demonstration sport, the event brought together hundreds of athletes from across Chungcheongnam-do province.

Preparing for this role required more than just swimming expertise. I spent weeks studying Paralympic swimming classifications, understanding different disability categories, and learning about adaptive coaching techniques. The theoretical knowledge I’d gained through sports psychology studies suddenly became practical preparation for real-world application.

The Korean Paralympic system impressed me with its organization and support structure. Unlike what I’d observed in Uganda, where adaptive sports infrastructure was still developing, Korea offered comprehensive classification systems, specialized equipment, and well-trained support staff. Yet I also noticed gaps—particularly in psychological support and motivational coaching for young athletes.

Meeting My Swimmers

The five young swimmers I was assigned to coach ranged in age from 8 to 15, each with different disabilities and swimming experience levels. There was Ji-hoon, a 12-year-old with cerebral palsy who had been swimming for three years; Min-a, a 10-year-old with visual impairment who was competing in her first major event; and Sung-woo, a 15-year-old amputee who had recently transitioned from running to swimming after a sports injury.

What struck me immediately was not their physical differences, but their shared determination and competitive spirit. These young athletes approached training with intensity and focus that rivaled any team I’d worked with. The psychological resilience they’d developed through overcoming daily challenges translated directly into athletic performance.

My role wasn’t to reinvent their technique—they had experienced technical coaches for that. Instead, I focused on the mental game: building race-day confidence, managing competition anxiety, and developing strategic thinking about pacing and tactics.

Adaptive Coaching Psychology

Working with Paralympic swimmers taught me that effective coaching required understanding not just physical adaptations, but psychological ones as well. Each athlete had developed unique mental strategies for overcoming their specific challenges, and my job was to help them apply those same strategies to competitive performance.

For Ji-hoon, whose cerebral palsy affected his muscle coordination, we worked on visualization techniques that helped him feel prepared for the inconsistencies he might experience during races. Rather than fighting against his condition, we developed race strategies that incorporated it—using his natural rhythm variations as tactical elements rather than seeing them as limitations.

Min-a’s visual impairment required different approaches. We spent considerable time on audio cues and spatial awareness, but more importantly, on building the trust and communication necessary for effective race guidance. The psychological aspect was crucial—helping her develop confidence in her guide and in her own navigation abilities.

Sung-woo’s recent transition from running presented interesting psychological challenges. His athletic identity had been disrupted by his accident, and swimming represented both opportunity and loss. We worked extensively on reframing his narrative from “former runner” to “developing swimmer,” focusing on the transferable mental skills he’d developed in track and field.

Competition Day Reality

May 29th brought the reality of Paralympic competition. The atmosphere at Seosan’s swimming venue was electric with nervous energy, proud families, and serious athletes preparing for their events. As a volunteer coach, I felt the weight of responsibility—these young swimmers had trained for months, and my job was to help them perform at their best when it mattered most.

The morning warm-up sessions revealed how different competitive coaching was from training preparation. Every athlete responded differently to pre-race nerves. Ji-hoon became quieter and more focused, needing gentle encouragement and reassurance. Min-a actually performed better under pressure, feeding off the competitive energy. Sung-woo required careful balance—enough activation to swim fast, but not so much that his technique broke down under stress.

Watching my swimmers compete was both thrilling and educational. The tactical discussions we’d had during preparation played out in real time. When Ji-hoon found himself in an unexpected lead at the 50-meter turn, he executed the race strategy we’d practiced for that scenario. Min-a’s communication with her guide was seamless, reflecting hours of trust-building work.

Beyond Performance: Building Community

One of the most valuable aspects of the competition was observing the community that Paralympic sports creates. Unlike some competitive environments I’d experienced, the Paralympic community emphasized personal achievement over comparative ranking. Athletes cheered for competitors from other cities, coaches shared training tips, and families formed supportive networks across disability categories.

This community aspect reinforced lessons I’d learned through Ubuntu Network work about the power of inclusive environments. When competition is structured to celebrate individual progress rather than just rankings, everyone benefits. Athletes push each other to improve while maintaining genuine support for their competitors’ success.

I found myself learning as much from other coaches as I was contributing to my own team. Experienced Paralympic coaches shared insights about long-term athlete development, managing training loads for different disability types, and the psychological stages that young Paralympic athletes typically experience as they develop competitive identity.

Technical Insights and Adaptations

The three-day competition provided intensive learning opportunities about adaptive swimming techniques and race strategy. Each event offered insights into how different disabilities require different tactical approaches. Watching the full range of Paralympic classifications compete helped me understand the nuanced ways that physical differences translate into competitive advantages and challenges.

The experience reinforced my belief that Paralympic sports represent the purest form of athletic competition. When athletes must overcome significant physical challenges to compete, every performance becomes an expression of determination, creativity, and mental toughness that goes far beyond typical sporting achievement.

Working with classification officials and technical judges also provided education about the complex systems that ensure fair competition across disability categories. The precision and fairness of Paralympic classification impressed me and highlighted the sophisticated infrastructure that supports elite Paralympic sport in Korea.

Performance Outcomes and Personal Growth

The competition results exceeded our expectations. Ji-hoon won gold in his classification’s 100m freestyle, setting a new personal best by over two seconds. Min-a placed third in her 50m backstroke, her first-ever Paralympic medal. Sung-woo, despite not placing in the top three, achieved his goal of breaking the two-minute barrier in the 100m butterfly.

But the real victories were psychological. Each athlete demonstrated growth in competitive confidence and tactical execution. More importantly, they began to see themselves as part of a larger Paralympic community rather than isolated individuals managing personal challenges.

For me, the experience provided crucial insights into the intersection of sports psychology and disability sport. The mental skills that serve Paralympic athletes—resilience, adaptability, creative problem-solving—were directly applicable to community development work I’d been doing internationally.

Connecting Local and Global Perspectives

The Paralympic coaching experience provided important perspective on my international community work. The systematic support available to Korean Paralympic athletes—professional coaching, quality facilities, competitive opportunities—highlighted what was missing in the Ugandan context where I’d been working.

Yet the fundamental psychological principles remained consistent across contexts. Whether working with Hope Hill School children learning to swim or Korean Paralympic athletes preparing for competition, the core elements were the same: building confidence, developing resilience, and creating supportive communities where individual strengths can flourish.

This realization would prove crucial as I prepared for my upcoming return to Uganda. The coaching techniques I’d refined working with Korean Paralympic athletes could be adapted for the inclusive sports programming I was planning for HopeHillBloom 2025.

Reflections on Inclusive Athletics

The three days in Seosan reinforced my belief that Paralympic sport represents the future of inclusive athletics. When competitive frameworks are designed to celebrate diverse abilities rather than privileging a narrow range of physical characteristics, sport becomes more meaningful for everyone involved.

The psychological insights I gained about motivation, goal-setting, and performance under pressure would directly influence my approach to community development work. The young swimmers I’d coached demonstrated that with appropriate support and opportunity, individuals facing significant challenges could achieve remarkable things.

Most importantly, the experience provided concrete evidence that the sports psychology principles I’d been studying academically had real-world application across cultural and ability contexts. Whether working with Korean Paralympic swimmers or Ugandan school children, the fundamental human needs for belonging, competence, and purpose remained consistent.

The confidence and practical experience gained through this coaching opportunity prepared me for the next phase of my international work, where I would need to integrate everything I’d learned about inclusive athletics, cross-cultural partnership, and community-based sports programming into comprehensive educational support systems.

The journey from Seosan’s Paralympic venues to Uganda’s Hope Hill School would require adapting Korean systematic approaches to Ugandan cultural contexts—a challenge that my growing understanding of sports psychology suggested was not only possible, but essential for creating truly sustainable community development partnerships.

Next: With enhanced understanding of Paralympic coaching principles and renewed confidence in inclusive athletics approaches, we prepare for our most ambitious international engagement yet, combining systematic sports programming with comprehensive educational support.

About this series: This post is part of my ongoing documentation of community engagement and sports-based advocacy work. Follow along as we explore the intersection of sports psychology, cultural exchange, and inclusive athletics.