Authors and affiliations: Sanghwan Park, Saint Johnsbury Academy Jeju

Abstract

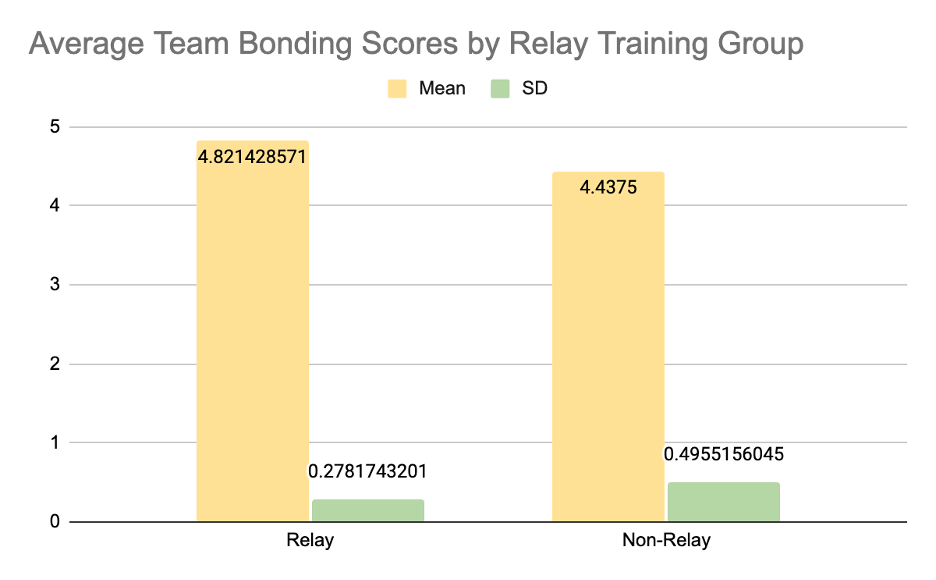

This study investigates the correlation between the enhanced sense of camaraderie among youth swimmers and their participation in relay training. Fifteen high school swimmers participated in the study by completing a four-item Likert-scale questionnaire that measured both the frequency of their relay training and their perceptions of team cohesion. Based on these responses, participants were classified into a Relay group (n = 7) and a Non-Relay group (n = 8). The Relay group reported both higher average bonding scores (M = 4.82, SD = 0.28) and less variation in their responses compared with the Non-Relay group (M = 4.44, SD = 0.50). When each survey item was examined separately, the Relay swimmers consistently scored higher, with the largest gap appearing on the statement, “Relay practices make me feel more connected to my team.” A scatterplot suggested a positive trend between the frequency of relay participation and cohesion scores; however, this difference was not confirmed statistically, as an independent-samples t-test did not reach significance (p = 0.086). Despite the limited sample size, the observed patterns indicate that synchronized, coordinated group training may have a psychological benefit. The findings support McNeill’s concept of muscular bonding and are consistent with prior research on the social effects of coordinated movement. This study has notable limitations, including its cross-sectional design, dependence on self-reported information, and the relatively small sample. Future studies should follow athletes over longer periods and involve participants from different sports and demographic groups. Even with these constraints, the results suggest that relay training may be linked to stronger perceptions of team cohesion among young athletes.

Keywords: Relay training, Team cohesion, Muscular bonding, Group dynamics

Introduction

A sense of connection with people in a group context can significantly impact one’s experience. It affects how well the team functions as a whole and also influences how much effort each person is willing to put in. One explanation for how these social bonds emerge is the concept of muscular bonding. Historian William McNeill introduced the idea of muscular bonding after noting that shared rhythmic activities—such as marching, chanting, or dancing—often strengthen the sense of connection among participants. These experiences can foster both a feeling of belonging and a collective purpose within the group ((McNeill, W. H. (1995). Keeping together in time: Dance and drill in human history. Harvard University Press.)). A comparable view was presented by sociologist Émile Durkheim through his concept of collective effervescence ((Durkheim, E. (1995). The elementary forms of religious life (K. E. Fields, Trans.). Free Press. (Original work published 1912))). He argued that group rituals and activities generate a shared emotional energy that deepens interpersonal ties and reinforces a collective identity. Such experiences allow individuals to feel more closely connected to one another and to develop a stronger sense of belonging.

Powerful relationships among teammates in athletic teams, especially among youth athletes, are often linked to enhanced communication, increased cooperation, and more emotional resilience ((Carron, A. V., & Brawley, L. R. (2008). Group dynamics in sport and physical activity. In T. S. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 213–236). Human Kinetics.)), ((Martin, L. J., Carron, A. V., & Burke, S. M. (2009). Team building interventions in sport: A meta-analysis. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review, 5(2), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2009.5.2.3)), ((Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.244)), ((Eys, M. A., Loughead, T. M., Bray, S. R., & Carron, A. V. (2009). Perceptions of cohesion by youth sport participants. The Sport Psychologist, 23(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.23.3.330)). Previous studies using the Group Environment Questionnaire have shown that higher levels of cohesion are linked to improved team communication and performance ((Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.244)). Research with young athletes has likewise reported that cohesion is positively related to perceptions of cooperation and collective efficacy ((Martin, L. J., Carron, A. V., & Burke, S. M. (2009). Team building interventions in sport: A meta-analysis. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review, 5(2), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2009.5.2.3)). Although swimming is often regarded as an individual sport, it also requires important elements of teamwork. Relay races highlight this point most clearly, as they require athletes to coordinate timing, maintain rhythm, and depend on one another’s reliability. Swimmers practice their starts, transitions, and pacing during relay practice so they can work as a team. These moments of coordination provide a meaningful opportunity for muscular bonding to take place. In this study, the construct assessed by the four-item scale aligns most closely with perceived team bonding, characterized as athletes’ subjective sense of emotional connection with their teammates. Sports psychology has shown increasing attention to team dynamics, yet little research has directly addressed the influence of synchronized movement on social bonding within swimming teams. Relay training, which involves repeated coordination and collective effort, has been especially understudied in relation to its potential to enhance teammate relationships. Most research on team bonding concentrates on organized team-building exercises, the relationships between coaches and athletes, or interactions occurring during competitions ((Martin, L. J., Carron, A. V., & Burke, S. M. (2009). Team building interventions in sport: A meta-analysis. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review, 5(2), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2009.5.2.3)). Thus, a deficiency persists in our comprehension of how routine training practices, such as relay exercises, may influence team cohesion.

This study aims to address the existing gap in the literature by examining the relationship between regular participation in relay training and enhanced perceived social bonds among high school swim team members. To examine this, a survey was employed to collect self-reported data regarding swimmers’ training practices and their perceived bond with teammates. By examining relay practice as a form of synchronized physical activity, this study seeks to clarify how the organization of training sessions may shape social cohesion within athletic teams. The hypothesis, based on the notion of muscular bonding, posited that swimmers engaged in relay training more regularly would possess more favorable impressions of team cohesion than those who participated less frequently.

Method

A cross-sectional, survey-based design was used in this study to examine whether participation in relay training is linked to stronger perceptions of team bonding among high school swim team members. This approach was chosen based on the idea that relay training involves coordinated physical movement and timing, elements that are central to the concept of muscular bonding. Muscular bonding, as defined by McNeill ((McNeill, W. H. (1995). Keeping together in time: Dance and drill in human history. Harvard University Press.)), refers to the feeling of cohesion that can arise from collective, rhythmic physical engagement.

Participants

Participants were selected from a high school varsity and junior varsity swimming team in Jeju, Korea. Swimmers were required to be aged 15 to 18 and actively participating on the team to qualify. There were 30 swimmers on the two teams, and 15 of them were chosen at random to be in the study. Fifteen people answered the survey. Participation was voluntary and kept confidential.

SurveyTool

The survey was developed and distributed using Google Forms. The study included three main elements: demographics, frequency of relay training, and perceived team cohesion. The demographic section collected data regarding the participants’ age, gender, and length of swimming experience.

To assess the frequency of relay training, swimmers were posed two questions: (1) the frequency of their participation in relay training sessions, scored on a 5-point Likert scale from “Never” to “Always”; and (2) if they consistently trained particularly for relay events, they replied with a yes or no.

There were four statements in the team bonding section that were meant to measure the physically and emotionally connected teammates felt to each other. A distinctive set of four survey questions was developed for this research to assess team bonding. These questions, which are detailed in Appendix A, were based on common thoughts regarding how to make teams work better together, instead of an existing validated scale. Participants evaluated their concurrence with statements such as “I feel a strong bond with my teammates during practices” and “Relay practices enhance my connection to my team,” utilizing a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Procedure

The survey was available for a duration of five days. The Google Form link was disseminated during practice through team communication channels and QR code pamphlets. IP addresses were not monitored, and responses were collected anonymously.

Data Examination

Participants were categorized into two groups for the study based on their replies to the relay training frequency question. Individuals selecting “Often” or “Always” were categorized as the Relay Group, while those choosing “Sometimes,” “Rarely,” or “Never” were classed as the Non-Relay Group. This categorization enabled a comparison between students with substantial relay training experience and those with little or no such proficiency.

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated for demographic variables and bonding scores. The mean bonding scores of the two groups were compared to ascertain if the relay group had higher average bonding scores. Additionally, a scatterplot was used to investigate the relationship between relay training frequency and average bonding score.

Results

In total, 15 swimmers participated in the survey. Based on self-reported frequency of relay training, seven were categorized into the Relay group and eight into the Non-Relay group. Team bonding scores were obtained by averaging four Likert-scale responses that captured athletes’ perceptions of cohesion and interpersonal connectedness.

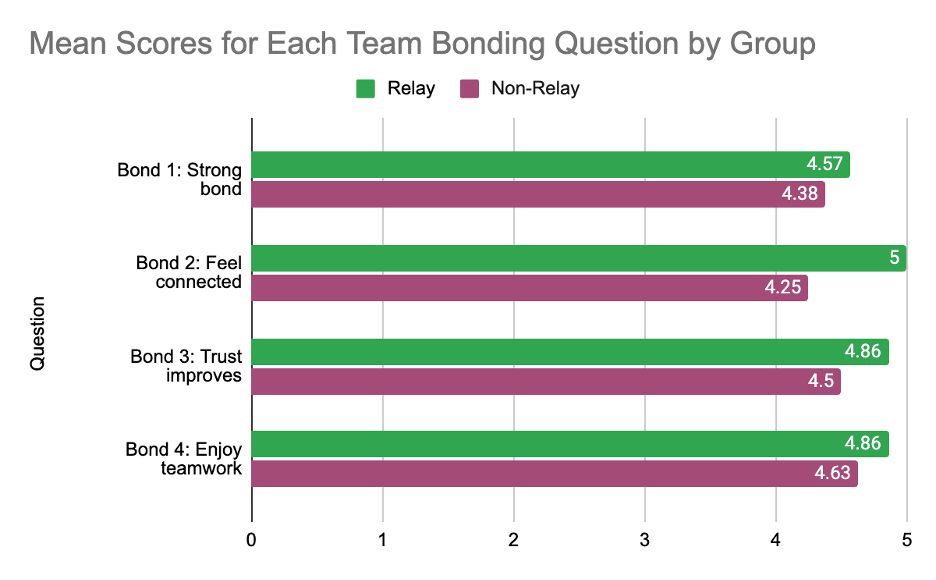

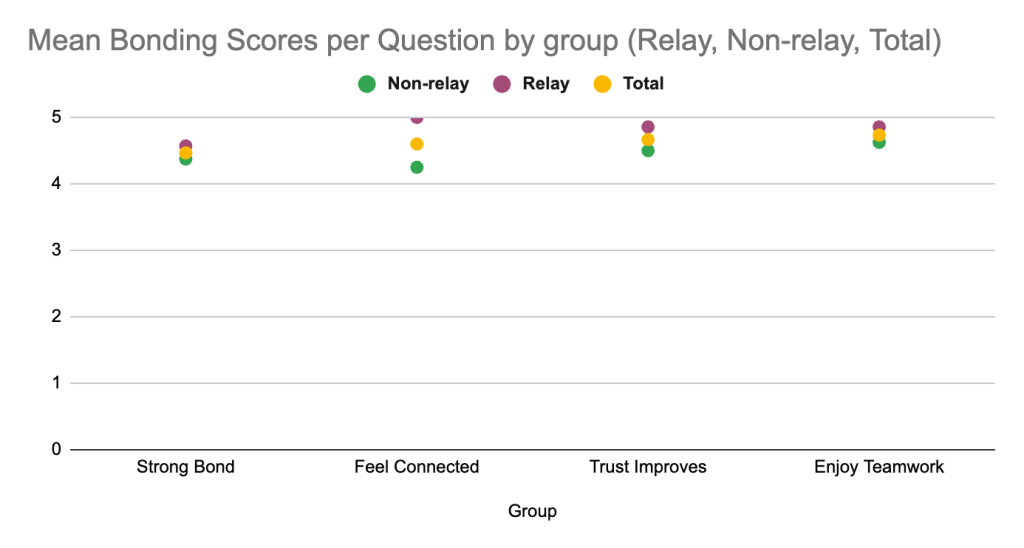

Figure 1 showed the average bonding scores for each group. The Relay group demonstrated a greater mean bonding score (M = 4.82, SD = 0.28) relative to the Non-Relay group (M = 4.44, SD = 0.50). Taken together, the findings imply that regular engagement in relay practice may contribute to heightened perceptions of team cohesion. To investigate the aspects of bonding that contributed to this discrepancy, each survey question was analyzed separately. Figure 2 depicts the mean score for each bonding item classified by group, while Figure 3 shows the same results alongside the overall average across both groups. The Relay group consistently achieved higher average scores on all four queries. The Relay group achieved a mean score of 5.00, while the Non-Relay group achieved a mean score of 4.25. The statement “Relay practices make me feel more connected to my team” showed the most significant difference. Supplementary items, including “I feel a strong bond with my teammates during practices” (Relay: 4.57, Non-Relay: 4.38) and “Working together in training improves our trust” (Relay: 4.86, Non-Relay: 4.50), exhibited minor yet persistent inconsistencies.

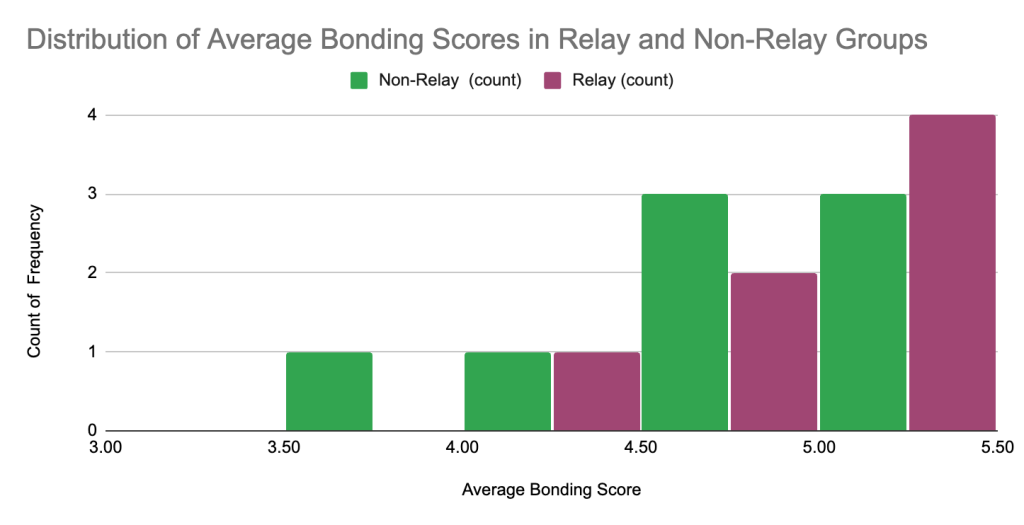

Figure 4 illustrates that bonding scores exhibited greater variability within the Non-Relay group, with certain participants recording scores below 4.0. The Relay group exhibited scores predominantly in the higher range (≥ 4.25), suggesting a higher level of perceived cohesion consistency. The smaller standard deviations observed in the Relay group support this difference in variability.

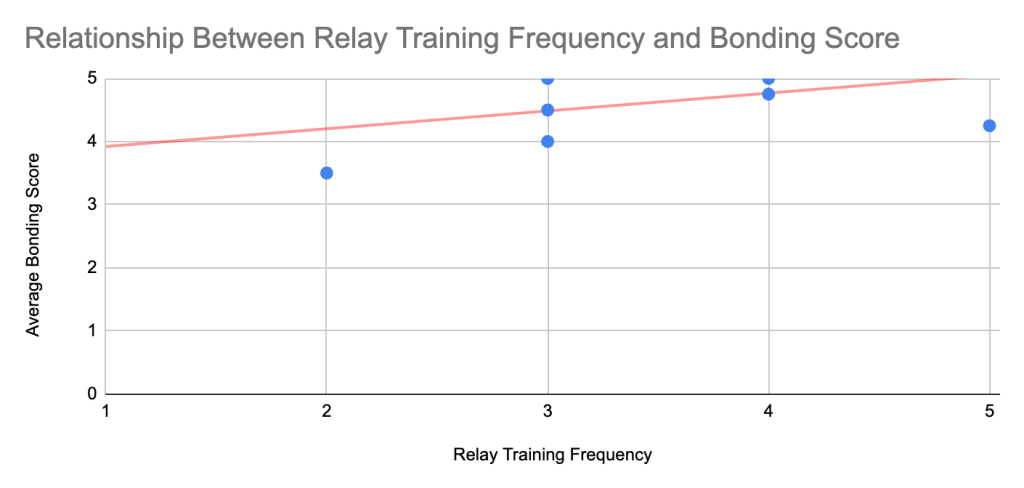

A scatterplot depicted the relationship between relay training frequency and bonding score, with the objective of analyzing the correlation between relay participation and team bonding (Figure 5). A slight positive trend suggested that swimmers who engaged more regularly in relay training exhibited stronger perceptions of team togetherness.

An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare average bonding scores between the Relay (M = 4.82, SD = 0.28, n = 7) and Non-Relay (M = 4.44, SD = 0.50, n = 8) groups. The difference was not statistically significant, t(13) = 1.88, p = 0.086. Nevertheless, the descriptive results indicated that swimmers who regularly participated in relay practice reported higher mean cohesion scores and less variability compared to those who did not. The Relay group had smaller standard deviations for most metrics, which means that swimmers who trained together in organized relay environments had more consistent bonding experiences.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between high school swimmers’ elevated perceptions of team cohesion and their participation in relay training. The results suggested a pattern that swimmers who engaged in relay practice on a regular basis experienced heightened feelings of group cohesion in comparison to those who practiced independently. This was illustrated by the Relay group’s increased mean bonding scores and the decreased variability in their responses, which suggested that this group had more consistent perceptions of team cohesion.

These results align with McNeill’s concept of muscular bonding, which posits that social cohesion is facilitated by shared rhythmic and synchronized movement. These data can be interpreted using McNeill’s muscular bonding theory, which highlights how coordinated physical activity promotes solidarity. The Relay group’s consistently superior cohesiveness ratings indicate that frequent, rhythmic synchronization during relay practice may initiate such bonding processes. Similarly, Durkheim’s concept of collective effervescence emphasizes how shared ritual-like acts can generate collective emotional energy, providing an additional perspective on the results. Future research could directly evaluate these theoretical frameworks by contrasting relay-based training with alternative forms of synchronized group exercise, ascertaining whether the observed effects are exclusive to swimming or generalizable across various sports. Relay training emphasizes timing, coordination, and mutual reliance, all of which contribute to fostering both physical and psychological connections among teammates. The assertion that “Relay practices make me feel more connected to my team” demonstrated the most notable difference at the group level, reinforcing the idea that these collaborative activities distinctly fortify interpersonal bonds. This finding is consistent with prior research indicating that synchronized group exercise enhances social bonds and collaborative behavior among participants ((Davis, A., Taylor, J., & Cohen, E. (2015). Social bonds and exercise: Evidence for a reciprocal relationship. PLOS ONE, 10(8), e0136705. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136705)). For instance, it has been demonstrated that team cohesion is influenced by group size in other athletic contexts ((Widmeyer, W. N., Brawley, L. R., & Carron, A. V. (1990). The effects of group size in sport. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 12(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.244)), and research on volleyball teams has similarly established connections between collective efficacy and cohesion ((Spink, K. S. (1995). Group cohesion and collective efficacy of volleyball teams. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 17(2), 129-139. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.2.129)). This implies that the patterns observed in swim teams may be applicable to other sports that necessitate synchronized coordination.

Figure 5 demonstrated a modest although persistent correlation between the frequency of relay participation and team bonding scores. While the results do not confirm causality, the trend indicates that heightened participation in coordinated training formats may foster improved perceptions of team cohesion and identification.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge various limitations. The small sample size (n = 15) limits the generalizability of the findings and hinders the possibility of conducting formal statistical analyses. The difference between the Relay and Non-Relay groups did not reach statistical significance, as evidenced by the t-test of independent samples (t (13) = 1.88, p = 0.086). Although the statistical test did not reach the threshold for significance, the descriptive results were too consistent to ignore. A clear pattern emerged wherein relay participants reported stronger and more uniform feelings of team cohesion. While the evidence offers a promising lead, the limited sample size restricts the strength of the conclusions. To address this, subsequent research should examine larger and more heterogeneous samples of athletes to verify the observed trend. Moreover, because the study relied on self-reported responses, the findings may have been affected by social desirability bias. The cross-sectional design presents a limitation by capturing data at a single time point, thereby restricting the ability to infer causal direction or assess the long-term effects of relay participation on team bonding. This study used a self-developed four-item measure that has not undergone validation to evaluate team cohesion. The findings’ reliability and generalizability are limited due to the lack of psychometric validation, despite the items being theoretically based on existing cohesion tests. Future research should either utilize validated instruments, such as the Group Environment Questionnaire, or conduct formal validation of novel measures. Furthermore, this study’s classification methodology has limitations. Participants were grouped into Relay and Non-Relay categories according to the frequency of relay training they reported, using subjective criteria (e.g., selecting “Often” or “Always”). This could have resulted in misclassification; for example, a swimmer who trained once a week but selects “Frequently” could have been categorized as a swimmer who trains daily. The precision of this classification is diminished, and it is recommended that future research incorporate objective measures of training frequency.

It is also important to consider alternative explanations. It is reasonable that swimmers’ decisions to participate in relays were influenced by pre-existing friendships or prior social connections among teammates, rather than the relays themselves directly enhancing team cohesion. Selection bias may have also been a factor, as athletes who were more motivated or socially inclined were more likely to participate in relay practices. Furthermore, the Relay group’s higher scores could be attributed to a greater emphasis on coaching or general team involvement. However, these alternative interpretations underscore the necessity of exercising caution when attributing discrepancies solely to relay participation.

Future study efforts should aim to validate these findings in larger, more diverse populations and across various athletic settings. Long-term research may clarify whether continuous participation in relay training promotes lasting improvements in team cohesion. Moreover, using qualitative interviews may provide deeper insights into how synchronized activities increase group cohesion.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research presents initial findings suggesting that relay training could yield psychological advantages in addition to enhancing physical performance by reinforcing feelings of team cohesion. The results underscore the promise of organized, collaborative training methods to improve team interactions in youth athletics. Coaches and educators looking to enhance team dynamics might explore the integration or expansion of relay-based activities within their standard training regimens.

Acknowledgments

I like to express my gratitude to my adviser for their direction during the research process, and to my teammates for their involvement and support in this project.

References

Carron, A. V., & Brawley, L. R. (2008). Group dynamics in sport and physical activity. In T. S. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 213–236). Human Kinetics.

Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7(3), 244–266. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.7.3.244

Davis, A., Taylor, J., & Cohen, E. (2015). Social bonds and exercise: Evidence for a reciprocal relationship. PLOS ONE, 10(8), e0136705. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136705

Durkheim, E. (1995). The elementary forms of religious life (K. E. Fields, Trans.). Free Press. (Original work published 1912)

Eys, M. A., Loughead, T. M., Bray, S. R., & Carron, A. V. (2009). Perceptions of cohesion by youth sport participants. The Sport Psychologist, 23(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.23.3.330

Martin, L. J., Carron, A. V., & Burke, S. M. (2009). Team building interventions in sport: A meta-analysis. Sport and Exercise Psychology Review, 5(2), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpssepr.2009.5.2.3

McNeill, W. H. (1995). Keeping together in time: Dance and drill in human history. Harvard University Press.

Spink, K. S. (1990). Group cohesion and collective efficacy of volleyball teams. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.12.3.301

Widmeyer, W. N., Brawley, L. R., & Carron, A. V. (1990). The effects of group size in sport. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 12(2), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.12.2.177

Appendix A. Survey Items for Team Bonding

Participants responded to the following four items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree):

- I feel a strong bond with my teammates during practices.

- Relay practices make me feel more connected to my team.

- Working together in training improves our trust.

- I enjoy training more when it involves synchronized teamwork.